By Darrell Staight

Ask anyone about a dive site that comes easily to mind and you can bet that it has some sort of feature that is unique amongst others. Whether it’s the aquatic life you’re likely to see, dramatic topography or stunningly clear water, something is likely to set it apart. For this entry I want to discuss a well known site in Mount Gambier. Ask divers about it and you can bet that one of the first things they are likely to mention is where it’s located. Allendale Cave is not located in a forest or the side of a hill or a coastline or even in someone’s paddock. No, it’s located slap bang in the middle of a road!

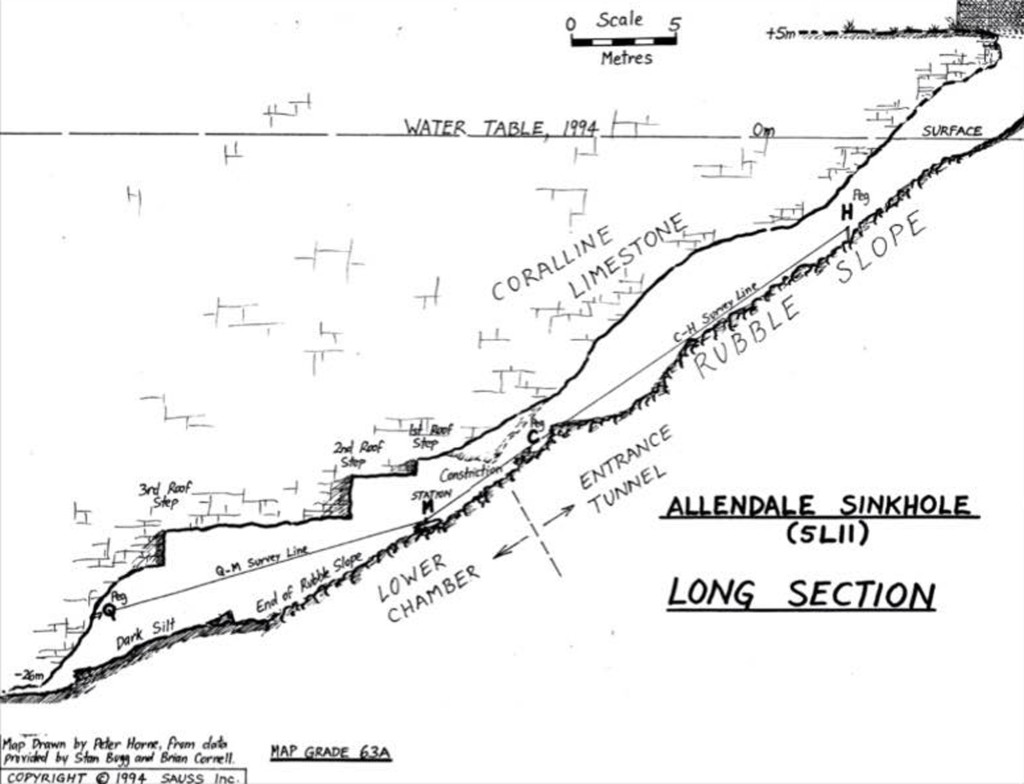

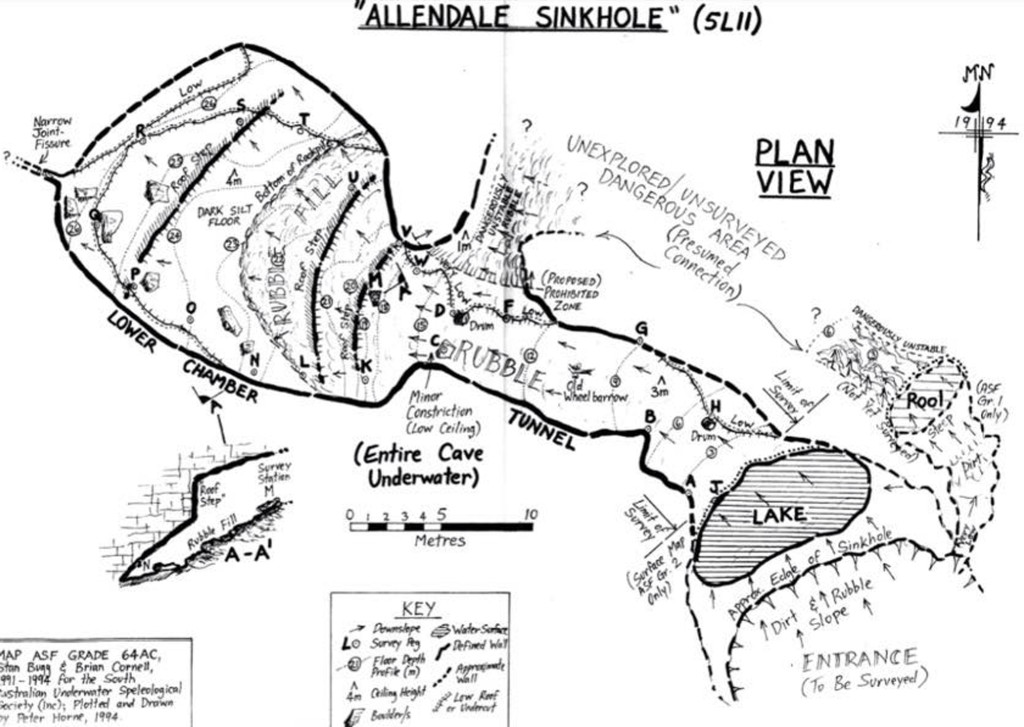

Like most South Australian Cave Divers I’ve had numerous dives at this site and apart from its unique location it doesn’t hurt that the water is normally stunningly clear. It’s not a huge site in comparison to some of the others, with a length of approximately 35 meters and a maximum depth of about 28 meters (assuming you don’t squeeze into a crack at the bottom which goes a little deeper). But it definitely has enough to hold a diver’s interest over the course of a dive.

The history of this dive site isn’t as clear as you might think, in fact anything before the mid 1900’s is pretty sketchy. I need to thank Peter Horne in particular, who has spent many years documenting the numerous cave diving sites, for kindly sharing some of the information with me and the work done by the Cave Exploration Group of South Australia (CEGSA) who were also a key reference for some of the early information. After all, diving is only part of the appeal. Much like wreck diving there is a real attraction to linking the past with the present and seeing how overhead environments change with time. If only the walls could talk, they would have some interesting stories to tell!

The site (and the small township it’s located in) is named after founder, William Allen Crouch with Allendale being derived from his middle name. What we do know is that the cave’s existence was known dating back at least to the 1800’s when it was used as a watering hole for bullock wagons using a hand pump and trough. However actual details of how the site looked back then are not really clear with no pictures that are known of available. All that’s known is some anecdotes that have been passed down over the years, like the site being originally discovered when a bullock and wagon allegedly disappeared into it and subsequently reappearing somewhere else. Although I have little doubt that the site probably did claim a few bullocks or even wagons over the years, I’m somewhat skeptical as to any subsequent re-appearances! We do know that the cave used to be larger in size, more closely resembling some of the other sinkholes you might find in Mount Gambier. It was described like a “cavity of a double tooth” with one passage heading in a south easterly direction and the other towards the Allendale Hall. This is reminiscent of other sites that have overhangs and/or passages leading from them and a central mound due to the initial collapse.

At some stage a decision was made to try and fill in the sinkhole, presumably with little knowledge of the extent of the water filled section, with the intention to build the road over it. Initially large boulders were brought in and later smaller loose ones. Despite over 9,000 tones being deposited into the site, it repeatedly opened up and eventually they gave up and the road remains around it with opposing lanes passing on either side. Only the one passage remains now, which is the one we dive in (the one described as heading towards the Allendale Hall) and there are no records of anyone ever diving the filled in side. Nor have any connections been found to what may or may not exist there.

When I first dived Allendale Cave, my initial impression of the site was of how steep it was. Entry is down a roughly cut rocky path and a rope is of benefit to hold on to in the event of slipping. Once in the entrance lake which is rather small, you descend down a similarly steep passage with the floor filled with loose rocks (the result of the attempted fill). The passage narrows somewhat before you emerge into a much larger chamber at the bottom. Assuming nobody has already stirred it up, the water is extremely clear and visibility is usually in excess of 30 metres. Light permitting, you will easily be able to see details from one side of this chamber to the other and this is normally where you spend most of your dive looking around. You will more than likely notice a stepped roof and that in this site there is also quite a bit of etched graffiti that was done during the earlier days of the CDAA (Cave Divers Association of Australia). In fact if you read through some of it you may even come across some that show some of the resistance to the formation of the Association and the subsequent regulation of diving activities. Shall we just say that at the time some people weren’t very happy and that’s evident in some of the comments! Whilst unsightly on one hand it does again link the past to the present and what was going on at the time.

At the deepest point is a small opening at the bottom. Initially described as a “crack in the rock”, a look inside shows that it’s no longer merely a crack but rather a very tight passage and not for the faint hearted should you consider squeezing into it. Divers are not encouraged to penetrate this feature but it’s a fair assumption that the opening of this crack was more likely caused by decidedly non-geological activity and probably has more in common with Charles Bronson’s character in ‘The Great Escape’ than what one generally associates with cave diving. Just a hunch (use your imagination. Underwater explorers are a determined bunch)!

As you ascend back up the steep slope of debris, if you didn’t notice it on the way in, you’ll find an interesting feature just after you leave the main chamber at approximately 12 meters. Off to what will now be your left you should see a tight flat passage. We appropriately call features like these ‘flatteners’ in cave diving. It’s pretty tight in here but if you dive in sidemount configuration like I do it’s actually reasonably easy to pass through without ending up covered in limestone. In fact you can almost do it without touching the roof or the loose rocks below if you are very careful. In the past this area was known to be extremely unstable with the rocky slope banked up on one site. To my eyes it actually appears reasonably ok now but it’s good to be mindful of how the rocks got there and not cause an avalanche by being reckless. I feel pretty comfortable drifting in, looking around and drifting back out. If you come out in clear visibility you know you did a reasonably good job negotiating it. If you look at the original map (by Stan Bugg and Brian Cornell) you can see that it’s speculated that this passage joins with a separate pool like feature (or what remains of it) to the side of the surface lake. However to my knowledge no connection has been made.

From there it’s back up to the entrance lake and out to warm up. Like most sites in Mount Gambier it’s a bit on the chilly side but I’ve not experienced it ever being less than 13 degrees. An hour or so in a decent exposure suit should be fine (nothing a decent cup of coffee or soup can’t fix anyway)! While you’re in the area it’s easy and convenient to fill your tanks at the Allendale Store which is literally just down the road and I’m rather fond of the hot dogs there too (every time I fill up I seem to end up getting one)!

Some months ago I put together a video of diving in Allendale Cave. I hope you enjoy it.